Discover, Learn, immerse, Connect

LIFE IN STILLS:

THE PEOPLE OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

“The sea, the great unifier, is man's only hope. Now, as never before, the old phrase has a literal meaning: we are all in the same boat.”

~Jacques Yves Cousteau

The Andaman & Nicobar Islands reside in popular perception in select ways.

The Archipelago is etched in popular memory as “Kala Pani ka Tapu” or the much dreaded exile that was imposed on political prisoners by the British.

The islands are also known for being a home to some of the last remaining “isolated tribes” of the world with “primitive” modes of existence.

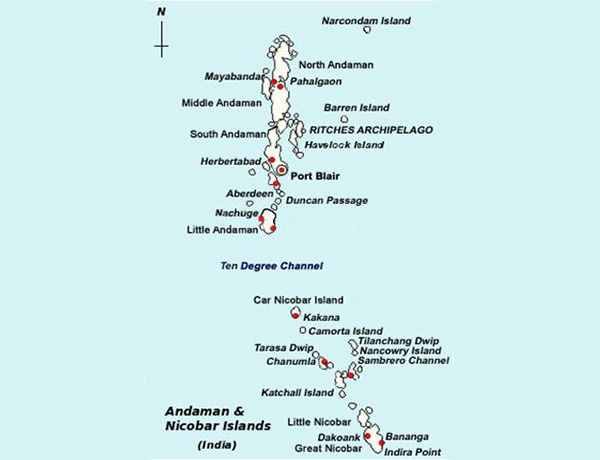

These islands lie to the South-East of the Indian subcontinent at the juncture of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

The remoteness of the Andaman and Nicobar Archipelago in relation to the mainland also contributes towards the lack of awareness regarding the islands among the common populace.

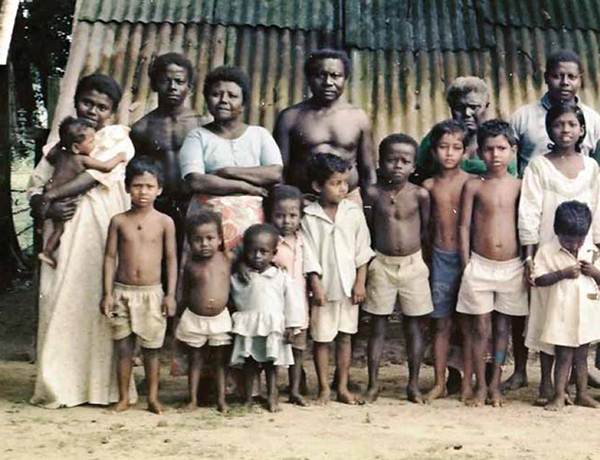

It is a little known fact that the demography of the Andaman and Nicobar islands is quite diverse. The islands are home to 6 indigenous tribes. The tribes combined, however, constitute only a minority of the total population. The majority of the population is formed by settlers and refugees who were brought by the British colonial government as prisoners and workers from various parts of the subcontinent. Owing to this great demographic diversity, the islands are often termed as “Mini India”.

The vicissitudes of history have not always been kind to its dwellers. The history of the people of these islands, (both the tribes and the settlers) represents a saga of war, toil and separation. The indigenous tribes today live in a precarious bubble of isolation, that is being increasingly threatened by external forces.

The coming of the British to the Andaman Islands in the 19th century changed the face of these islands forever. An alarming majority of indigenous tribes perished due to wars and diseases that the colonials brought in their trail.

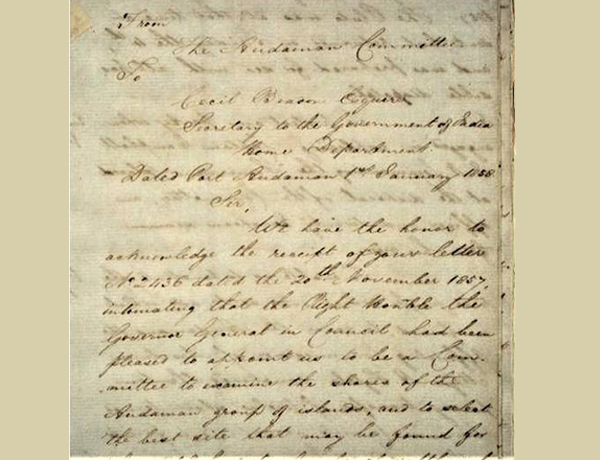

On the left: The Andaman Committee Report recommending the establishment of the settlement on Port Blair, 15th January, 1858.

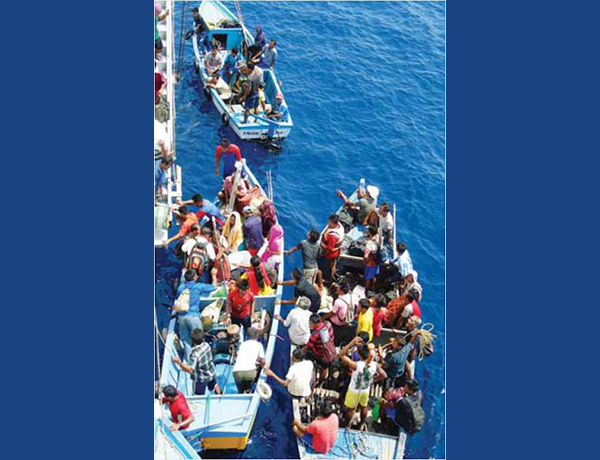

In the last couple of decades, the Andaman and Nicobar islands have become a hub of tourist activity.

Tourists are lured to the islands by the promise of catching a glimpse of the “primitive humans” and “sky-clad people”. The visitors often engage in intrusive acts that disrupt the lives of the indigenous people.

In recent times, the government has conscientiously restricted “tribal tourism” that treats the “exoticity” of these vulnerable groups as a marketable commodity. The government has also banned photography and videography in protected areas.

The Andaman and Nicobar islands are home to six indigenous tribes: the Great Andamanese, Jarawa, Onge, Sentinelese, Shompen, and Nicobarese. Of these, the first five are collectively known as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs). They enjoy protected status and exist in varying degrees of isolation from the outside world.

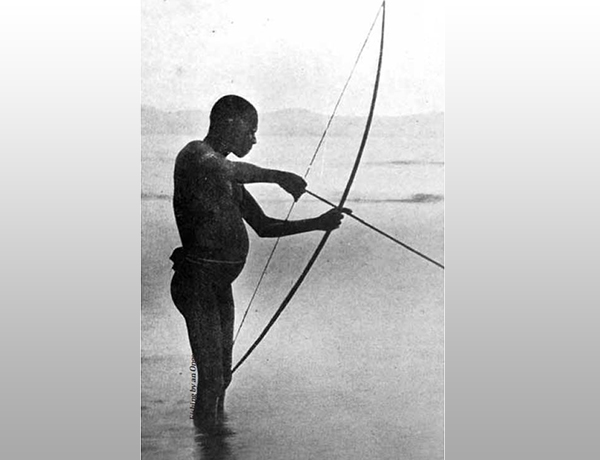

The advent of these tribes in the Archipelago is unknown and shrouded in mystery. Scholars believe that these islands were first inhabited as early as the Mesolithic period. The Great Andamanese, Jarawa, Onge and Sentinelese are held to be of Negritoid origin. The Shompen and the Great Nicobarese on the other hand are of Mongoloid stock. It is a matter of great fascination as to how these tribes survived in complete isolation from the rest of the world for thousands of years.

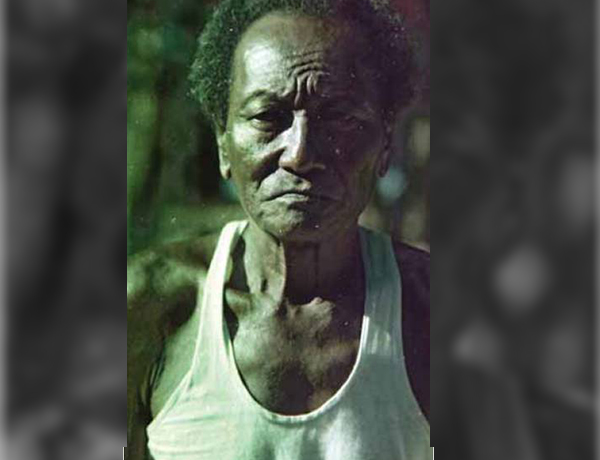

ANDAMANESE

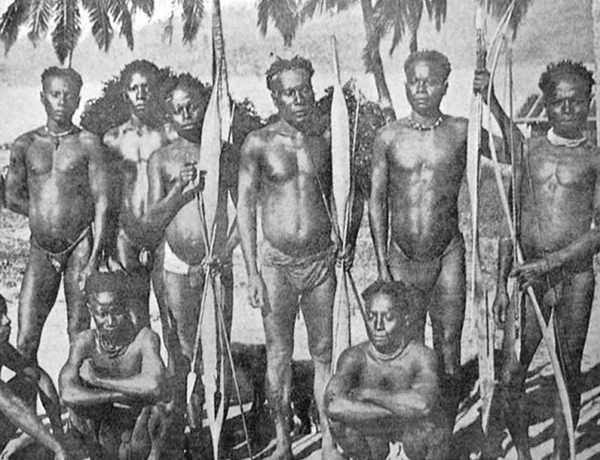

The Great Andamanese were originally a hunter-gatherer tribe of Negrito origin that used to be distributed over the entire stretch of the Andaman Islands. Colonial incursion in the 19th century had a devastating impact upon this tribe pushing it to the brink of extinction through war and disease. The remaining members of the tribe were relocated to Strait Island (North & Middle Andaman) in 1969.

The Great Andamanese have now completely given up on their hunting-gathering lifestyle and accepted modern amenities like concrete houses and commodities of daily usage from the Andaman Administration.

Despite having been assimilated into a modern way of life, the Andamanese have held on strongly to their religious and spiritual beliefs. The Great Andamanese believe in the power of various benevolent and malevolent spirits. They also worship their ancestors and depend upon them to negotiate with these spirits.

ONGE

The tribe derives its name from the Onge word en-iregale meaning “perfect man”.

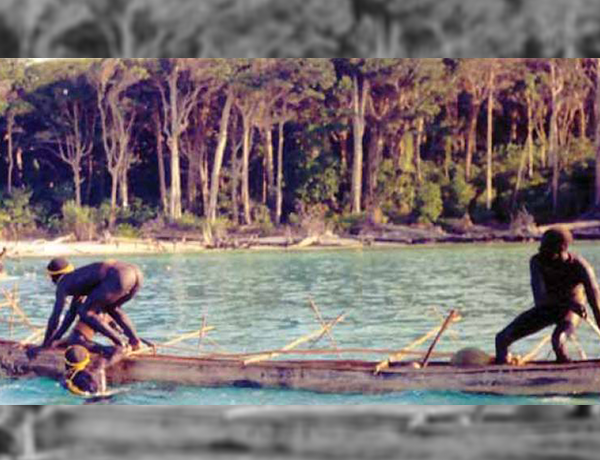

They are hunter-gatherers and up until recent times depended entirely on their immediate environment for resources. The Onge inhabit the Little Andaman island.

The society is based upon communal hut-based exogamous groups or bands. The Onge do not marry outside their tribe and practice monogamy.

The livelihood of the Onge mainly revolve around hunting wild boars, turtles, collecting honey and fishing. The most important ritual is Tanagiru or the adulthood ritual in which an Onge boy on the threshold of manhood has to prove his skill in hunting boars.

Today, Onge children have started receiving modern education.

JARAWA

The Jarawa are classic hunter-gatherers who inhabit the western part of the South and Middle Andaman Islands. They have became friendly with non-Jarawa populations only very recently.

They have a broad resource base which includes around 150 species of plants and animals. The majority of the resources are season-specific. Both men and women participate in foraging.

As a hunting-gathering community, the Jarawa are nomadic and move from one place to another in search of resources.

Jarawa women love to engage in leisure activities that involve making garlands, waist girdles, armlets and headbands from leaves, flowers, shells, cowries and cotton thread.

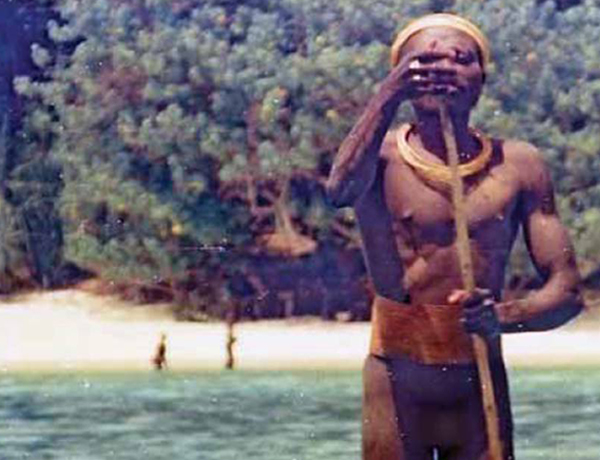

SENTINELESE

The Sentinelese are the last remaining truly isolated tribe in the world. These fearless and proud people have always fiercely rejected attempts by outsiders to establish contact with them. They inhabit the Northern Sentinel Island of the Andaman Archipelago.

It is not known what the Sentinelese call themselves or what their perception of “outsiders” is. Beginning from 1967, the Government had repeatedly attempted to make contact with them, and these contact expeditions lasted till 1994. Some debated the merit of trying to establish contact with a people who were happy and healthy in their isolation. The Government has since followed a no-contact stance, except for vigils at the event of natural calamities to assess their well-being.

It is remarkable that the Sentinelese survived the Tsunami of 2004. The disaster brought about widespread devastation and caused the underwater coral reefs of the Sentinel Islands to become exposed and become permanently dry land. It is believed that ancient wisdom of the sea helped these tribes to survive the disaster.

SHOMPEN

The Shompen live in relative isolation in the tropical rainforests of the Great Nicobar Island. The term “Shompen” is derived from the word sam-hap which means jungle dwellers in Great Nicobarese.

The Shompen engage in occasional barter with the Great Nicobarese, their coastal neighbours. The relationship between the Shompen and the Great Nicobarese over time has been one of conflict, compromise and co-existence.

The Shompen are shy and distant but less hostile than other tribes such as the Jarawa and Sentinelese. The Tsunami disrupted the resource channels of this tribe by compelling a large number of Great Nicobarese to relocate. This gap has been filled by other ethnic tribes. The interaction of the Shompen with government welfare agencies is still at a rudimentary stage.

NICOBARESE

All the indigenous groups inhabiting the Nicobar Islands are collectively known as the Nicobarese. They, however, identify themselves as Tokasato which means “one who wears infinitesimal loin cloth”.

The livelihood of the Nicobarese is dependent on fishing, hunting, pig rearing and coconut plantation.

The wooden effigy plays an important ritual role in the lives of the Nicobarese. It acts as a medium to channelize the power and blessings of the spirits of their ancestors. The menluana or the priest assists in establishing communication with the spirit world. The priest is also the bearer of traditional wisdom of the Nicobarese.

The British colonials altered the fortunes of the Andaman Archipelago for good. Apart from having a calamitous effect on the indigenous tribes, the British also introduced new sections of people to the Islands whom they brought in as prisoners and labourers from various parts of the mainland. Many such groups as the Moplahs, Bhantus, Karens and Ranchiwalas stayed on and became permanent inhabitants of the land.

MOPLAHS

The Moplah or Mappila Rebellion of 1929 that took place in Malabar was suppressed by the British with an iron hand. A total of around 1400 prisoners were deported to the penal colony in the Andamans. In order to eradicate the revolt completely, the British resorted to what is termed as the “Moplah scheme” whereby many prisoners, after the completion of their sentences, were given agricultural tickets and encouraged to settle in the Islands.

These prisoners, after their period of deportation was over, brought their families over from the mainland and settled down in South Andamans. Moplah villages in the Andamans are named after place names in Kerela such as Mannarghat, Malappuram, Calicut, Tirur, Manjeri and Wandoor. The Moplahs of the Andamans today live in close-knit communities and still follow their traditional customs and way of life.

BHANTU

The Bhantu were among the groups declared as “Criminal Tribes” by the British in 1911. After executing their leader, the followers were brought to the Andamans as “convicts”. The British later sought to resettle these people as “Free Settlers” on the Islands by providing them with land and money.

The Bhantu identify themselves as of Rajput origin and as descendants of the soldiers of Rana Pratap Singh of Chittorgarh (1540-1597). Initially, after being settled on the Islands, they took up agriculture. The newer generations, however, aim for government and administrative jobs. The Bhantu have also adopted many customs and manners of their neighbouring communities and developed a unique culture of their own. Today, the majority of Bhantus are settled in Caddlegunj and Aniket in South Andaman district.

KAREN

The Karens were brought to the Andamans by the British in the early part of the 20th century as labourers to clear patches of dense forests to make it habitable . While the Karens were brought from Burma, it is believed that they originally belonged to Central Asia.

Many settled down for good and intermarried with neighbouring groups such as Bhantu, Ranchiwalas and Great Andamanese. Today, most of them reside in the Mayabunder area of Middle Andaman. The social customs, traditions and way of life of the Karens have greatly altered as a result of this intermingling.

RANCHI

The Ranchi or Ranchiwalas were brought by the British to the Andamans in 1906 from the Ranchi and Chhotanagpur region of India, to clear dense forests. Ranchi is a generic name for different tribes such as the Oraon, Munda, Kheria, Baraiks, Lohars and Kumhar from the Chhotanagpur plateau in India.

The Ranchiwalas after settling on the Islands initially worked as wage labourers in the forest department, and timber and marine industries. A sizeable portion of the population resides in Baratang Island of North and Middle Andaman. Today, a great deal of heterogeneity exists within this group in terms of income and employment. Although this group has assimilated itself well into the composite culture of the Andamans, they still look up to their native land with a sense of nostalgia and belonging.

If once you have slept on an island

You’ll never be quite the same;

You may look as you looked the day before

And go by the same old name,

You may bustle about in street and shop;

You may sit at home and sew,

But you’ll see blue water and wheeling gulls

Wherever your feet may go.

You may chat with the neighbors of this and that

And close to your fire keep,

But you’ll hear ship whistle and lighthouse bell

And tides beat through your sleep.

Oh, you won’t know why, and you can’t say how

Such change upon you came,

But – once you have slept on an island

You’ll never be quite the same!

~ Rachel Field

Government of India

Government of India